Business is creating new forms of English

The Financial Times December 26, 2013

'The academic view is that native speakers have no authority over what is right or wrong'

The academic view is that native speakers have no authority over what is right or wrong

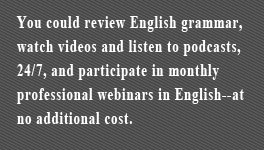

Bridgestone, the Japanese tyremaker, has announced that it is making English its official language, joining Rakuten, also Japanese, Lenovo of China and European companies such as Nokia and Airbus.

But whether they make an official announcement or not, English is now part of the day-to-day life of any business with international operations, used almost every time people have a conversation with someone whose language they do not share.

These interactions are often uncomfortable and tiring (Bridgestone says it will implement its new policy gradually). Business people have responded by creating their own forms of English - and they are changing the way the language is spoken.

I heard about some of these new practices at a seminar last week at the University of Southampton, which, with its Centre for Global Englishes, has been bringing together some of the most interesting researchers in the field.

Several have been following managers at work in Germany, Saudi Arabia, the UK and other countries, and noticing the ways in which they use English. Some have already published their conclusions; others are still working on them.

But it is clear that world business English has several features.

First, people don't abandon their own languages at work, even in large groups. While researchers have found cases of Finnish, Dutch or German managers continuing to speak English even when everyone in the room has the same mother tongue as they do, others recognise the absurdity of the situation.

Susanne Ehrenreich of the Technical University of Dortmund, one of the seminar presenters, had already described, in a 2010 article for the Journal of Business Communication, a case of German managers realising everyone else had left. One said: "It would actually be much easier if . . . we continued the conversation in German."

At the seminar, Prof Ehrenreich also referred to a group of Italian managers, in discussion with Germans, interrupting the English conversation to confer with each other in Italian.

Japanese business people, in my experience, do this too. Adam Jones, the editor of this page, has suggested we call these conversations "mother tongue breakouts".

Nuha Alharbi of King's College London, who spent two months studying language use in the information technology department of a Saudi health insurance company, noticed that, even though the multinational staff spoke English to each other, they incorporated Arabic words into their conversation. "It's not a big mushkila [problem]," a Tagalog speaker told his colleagues.

This is a useful way to learn the local language. In my first job in journalism, in Athens, everyone else in the office was bilingual, allowing me to expand my vocabulary when they used Greek words and phrases. (They always swore in Greek.)

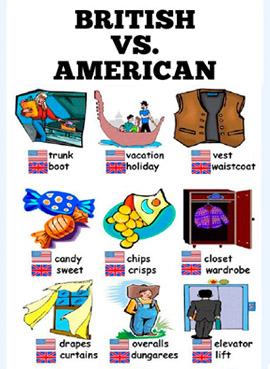

On the other hand, Prof Ehrenreich noticed that German managers used English phrases such as "joint venture" and "sales price" even when speaking to each other in German. Asked whether they knew what the German equivalents were, they had to stop and think about it.

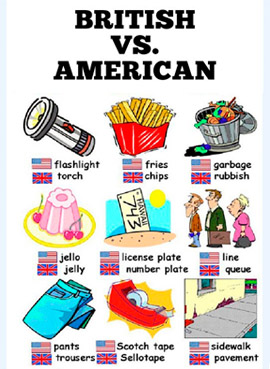

One seminar participant spoke about non-English speakers creating their own words. A group of European food retailing managers had, for months, been talking about staging "degustations".

This French-derived word is in English dictionaries, although not widely used, and they stopped when an Australian joined their discussion and said he didn't know what they were talking about. He told them the word they were looking for was "tastings".

Participants at the Southampton seminar thought this was wrong; the academic view is that native English speakers have no authority when it comes to deciding what is right or wrong. It appears natural to me that people learning a language turn to native speakers for advice, but that is not going to stop non-native speakers creating their own words when speaking English.

Native speakers are, as I have heard many times before, a problem in the new world of business English. In the Saudi company Ms Alharbi studied, the chief executive's personal assistant, a Palestinian, asked to be excused from taking minutes because she could not understand what the native English speakers were saying - they talked too quickly and in "strong accents".

+7 (495) 969-87-46

+7 (495) 969-87-46