"Crazy English" Teacher Admits to Domestic Violence

The New Yorker August 28, 2013

Published by EVAN OSNOS

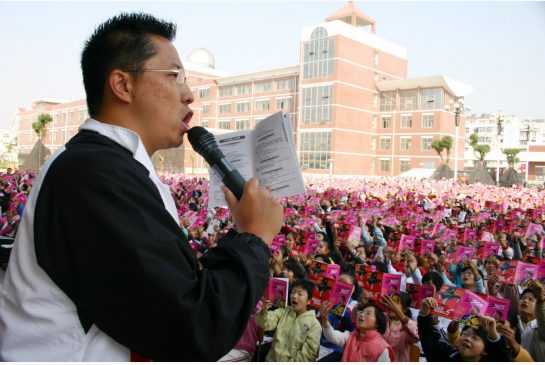

Accompanied by his photographer and his personal assistant, Li Yang stepped into a Beijing classroom and shouted, "Hello, everyone!" The students applauded. Li, the founder, head teacher, and editor-in-chief of Li Yang Crazy English, wore a dove-gray turtleneck and a black car coat. His hair was set off by a faint silver streak. It was January, and Day Five of China's first official English-language intensive-training camp for volunteers to the 2008 Summer Olympics, and Li was making the rounds. The classes were part of a campaign that is more ambitious than anything previous Olympic host cities have attempted. China intends to teach itself as much English as possible by the time the guests arrive, and Li has been brought in by the Beijing Organizing Committee to make that happen. He is China's Elvis of English, perhaps the world's only language teacher known to bring students to tears of excitement. He has built an empire out of his country's deepening devotion to a language it once derided as the tongue of barbarians and capitalists. His philosophy, captured by one of his many slogans, is flamboyantly patriotic: "Conquer English to Make China Stronger!"

Li peered at the students and called them to their feet. They were doctors in their thirties and forties, handpicked by the city's hospitals to work at the Games. If foreign fans and coaches get sick, these are the doctors they will see. But, like millions of English learners in China, the doctors have little confidence speaking this language that they have spent years studying by textbook. Li, who is thirty-eight, has made his name on an E.S.L. technique that one Chinese newspaper called English as a Shouted Language. Shouting, Li argues, is the way to unleash your "international muscles." Shouting is the foreign-language secret that just might change your life.

Li stood before the students, his right arm raised in the manner of a tent revivalist, and launched them into English at the top of their lungs. "I!" he thundered. "I!" they thundered back.

In fact, the ACT has pulled ahead for the first time: 1,666,017 students took the ACT last year; 1,664,479 took the SAT.

One by one, the doctors tried it out. "I would like to take your temperature!" a woman in stylish black glasses yelled, followed by a man in a military uniform. As Li went around the room, each voice sounded a bit more confident than the one before. (How a patient might react to such bluster was anyone's guess.)

To his fans, Li is less a language teacher than a testament to the promise of self-transformation. In the two decades since he began teaching, at age nineteen, he has appeared before millions of Chinese adults and children. He routinely teaches in arenas, to classes of ten thousand people or more. Some fans travel for days to see him. The most ardent spring for a "diamond degree" ticket, which includes bonus small-group sessions with Li. The list price for those seats is two hundred and fifty dollars a day - more than a full month's wages for the average Chinese worker. His students throng him for autographs. On occasion, they send love letters.

There is another widespread view of Li's work that is not so flattering. "The jury is still out on whether he actually helps people learn English," Bob Adamson, an English-language specialist at the Hong Kong Institute of Education, said. The linguist Kingsley Bolton, an authority on English study in China, calls Li's approach "huckster nationalism." The most serious charge - one that in recent months has threatened to undo everything Li has built - holds that the frenzied crowds, and his exhortations, tap a malignant strain of populism that China has not permitted since the Cultural Revolution.

"I have seen this kind of agitation," Wang Shuo, one of China's most influential novelists, wrote in an essay on Li. "It's a kind of old witchcraft: Summon a big crowd of people, get them excited with words, and create a sense of power strong enough to topple mountains and overturn the seas."

Wang went on, "I believe that Li Yang loves the country. But act this way and your patriotism, I fear, will become the same shit as racism."

The global headquarters of Li Yang Crazy English holds about two hundred employees (another two hundred work nationwide) and sprawls across four floors of an office building in the southern city of Guangzhou. Li is rarely there. He likes hotels. Even in Beijing, where he shares an apartment with his wife and their two daughters, he often keeps a hotel room nearby so that he can work without distraction. (A third daughter from a previous marriage lives with her mother in Canada.)

For several days this winter, Li and his lieutenants were ensconced in the presidential suite on the top floor of Guangzhou's Ocean Hotel. The suite was furnished in a modern clubby style: a faux fireplace, white leather couches, a cavernous Jacuzzi, a large wooden model of a schooner. Fresh air was needed. Li had just wrapped up an annual marathon of meetings with managers from around the country, and a dozen young men and women were huddled, heavy-lidded, over laptops. He fiddled with the thermostat and threw open the curtains to reveal a view, from the twenty-sixth floor, of dun-colored apartment blocks and blue-glass high-rises twinkling in the sun.

He sat down on a couch and began explaining to me a list of new projects, including a retail plan that would create, in his words, the Starbucks of English education. "People would get off work and just go to the Crazy English Tongue Muscle Training House and then go back home," he said. "Just like a gym."