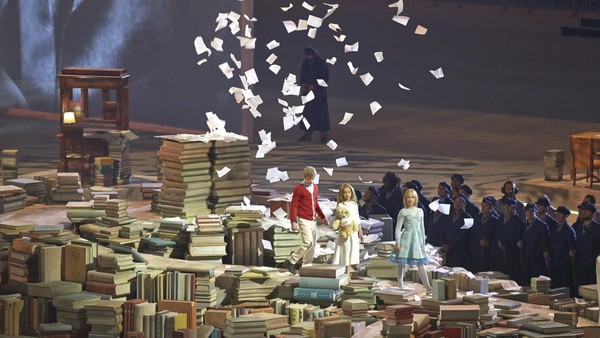

Reasserting Russia's literary status

The Financial Times May 5, 2014

Can the new generation of writers revive a great tradition?

Once upon a time it was the greatest literature in the world. When William Faulkner was asked to name the three best novels of all time, he cited the book Dostoevsky described as “flawless”: “Anna Karenina, Anna Karenina, Anna Karenina.”

In rankings of the world’s literary greats, Russia tends to figure more prominently than any other country. Anna Karenina, War and Peace, the stories of Anton Chekhov and Lolita (written in English and self-translated into Russian) are unfailingly on such lists, alongside Shakespeare, Proust, F Scott Fitzgerald, Mark Twain, Flaubert and George Eliot. And that’s without even mentioning Gogol, Pushkin, Turgenev, Pasternak and, of course, Dostoevsky, the writer who did down-to-earth plain-speaking just as beautifully as Tolstoy did lofty spirituality. From Notes from the Underground: “I say let the world go to hell but I should always have my tea.”

Where, though, are today’s equivalents? The question is of more than academic significance. Last December, Vladimir Putin convened a “Literary Assembly” featuring descendants of Pushkin, Dostoevsky and Tolstoy (whose great-great-grandson Vladimir is the Russian president’s cultural adviser). Putin declared that there was “a responsibility to global civilisation to preserve Russian literature” and expressed dismay that Russia could no longer boast of being “the best-read country in the world”. “Russians spend an average of only nine minutes per day reading books, and that figure is decreasing,” he said. “I think that declaring 2015 the Year of Literature in Russia is worth thinking about.” Recent events seem to have put that idea on ice.

Still, some see Russian literature as on the cusp of a recovery, pointing to the success of writers such as Mikhail Shishkin (compared to Nabokov and Chekhov) and Lyudmila Ulitskaya, the first woman to win the Russian Booker, the country’s leading prize for fiction. “Russian literature is healthy. It’s probably the healthiest part of Russian society, actually,” says Vitali Vitaliev, a writer and long-term UK resident (he defected in 1990). “To paraphrase Tolstoy: writers need a bit of hardship. You don’t want to be sentenced to death in order to be creative. But there is a huge internal protest at Putin’s power.”

Perhaps the effects of this are not yet fully evident, though, as many of the popular literary books in Russia at the moment are definitely not critiques of the regime. Instead they come under the awkward label “fantasy”. The post-Soviet dystopias of Viktor Pelevin, Vladimir Sorokin and Dmitry Bykov – all feted at home and with a small but enthusiastic audience abroad – fit into this genre. Other big sellers include Sergei Lukyanenko, the sci-fi author best known for his vampire blockbuster Night Watch (1998), and Boris Akunin, whose literary Erast Fandorin detective stories intentionally channel Sherlock Holmes by way of Dostoevsky.

Akunin is sceptical about claims of a reassertion of Russia’s literary status. This may be because he refuses to read contemporary novelists himself. “I’ve been reading only non-fiction something like 15 years,” he says by email from Moscow. “I believe it’s not healthy to read other people’s writing when you write yourself. But my wife reads everything and she says that, no, we are not in good shape. There is an occasional spark. But as a whole the landscape is depressing.”

“Why don’t I engage with the contemporary context?” Akunin wonders. “I do. But not in fiction. I write in my blog about everything that interests me – directly, without fictionalising.” (Typical extract: “I would enjoy talking to Putin about literature after all the political prisoners are released. Until then, it is not possible.”) “Fiction is for me, well, fiction. A territory for games and imagination, not to be taken too seriously. Probably a lot of my compatriot authors feel the same way, which might be the answer to the question as to why Russian literature is less than great.”

Many of the most inspiring new names, such as Elena Chizhova, are re-examining the past rather than taking on the present. Her novel The Time of Women (published in the UK by Glagoslav), which won the Russian Booker in 2009, tells the story of three elderly women raising a child in a communal apartment in the 1960s. “People are searching for some moral bearings, and it’s easiest to find that in the lives of your own grandmothers,” she said in 2010. “Theoretically, we consider that there are no decent people in Russia, but empirically we can show that they used to exist”.

Pavel Basinsky, Russia’s biggest 21st-century non-fiction star, told me at last month’s Pen Literary Salon at London Book Fair that authors face a unique challenge in Putin’s Russia, where their work – notwithstanding events such as the Literary Congress – is simultaneously completely free and completely ignored: “Literature doesn’t trouble the authorities. They don’t consider that it has power, so they don’t read it.” Most of the best contemporary writers, he intimated, were toiling on apolitical fiction away from the spotlight. Basinsky started research on his prizewinning 2010 biography of Tolstoy, to be published this year in English translation, in reaction to a television poll that put Stalin at number three in a list of Great Russians and Tolstoy at number 40 (“although at least Dostoevsky and Pushkin were in the top 20,” he notes).

Evgeny Reznichenko, director of Russia’s not-for-profit state organisation the Institute of Translation, was recently in London for a series of Read Russia events celebrating the 2014 Russia-UK Year of Culture. “People abroad just don’t know Russian contemporary authors,” he admits. “So it’s great that we have Basinsky writing about Tolstoy. When the name of a great Russian author comes up, it still attracts international attention. But it has been more difficult for contemporary authors since the 1990s because suddenly everything from the previous three decades was published at once.”

Reznichenko sees a potential international favourite in Zakhar Prilepin. His Chechnya war novel Sin (2007) was named as “the book of the decade” by Russia’s National Bestseller Prize jury, yet it only became available in English in 2012. This is another problem for Russian literature: quality translation into English is painfully slow. Basinsky mentions that it took a year for the German translation of his book to come out. The English translation has taken three.

In the UK we’re still catching up with overlooked geniuses from the Soviet era. The translator Robert Chandler’s work on Andrei Platonov and, even more significantly, Vasily Grossman has gone a long way to restoring them to their rightful place in the Russian canon. Currently in demand at The Russian Bookshop at Waterstones’ Piccadilly branch – a key marker of the buoyancy of Russian literature in Britain – is a much-praised recent translation of Sergei Dovlatov’s 1983 autobiographical comic classic Pushkin Hills, about an alcoholic writer who becomes a tour guide for Pushkin pilgrims.

Recovering from the psychological legacy of the Soviet era was never going to be easy, says Vitaliev. “In the times of perestroika, honest reading was almost a more challenging occupation than honest writing. I would pay my monthly salary to get hold of Baudelaire. Books were displayed next to the family silver. They were something to show off. The lives of many intelligent people revolved around finding good books. I had Orwell’s 1984 for one night once and then had to pass it on. The next morning I was in tears. You don’t forget such stuff.”

+7 (495) 969-87-46

+7 (495) 969-87-46