How to say om nom nom in Hungarian, and other onomatopoeic insights

All languages have words that imitate sounds in the real world. But how does a French dog bark, and a Turkish duck quack?

The New York Times January 18, 2014

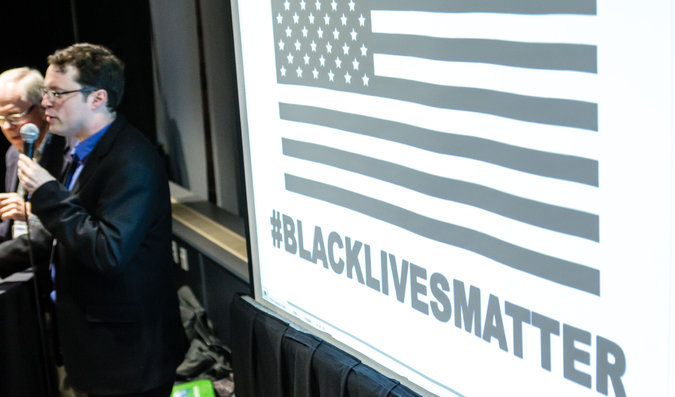

The hashtag #blacklivesmatter was selected as the winner of the American Dialect Society’s Word of the Year competition for 2014. Credit Dan Cronin for The New York Times

PORTLAND, Ore. — “It is a solemn and important duty we have,” Allan Metcalf, a grandfatherly looking man, said into a microphone. He was standing in front of a crowd of the nation’s top linguists, many of whom were still flooding into the already packed room. The space was tight, Mr. Metcalf apologized, but the linguists had only an hour. They had to get started.

“What happens after this?” I whispered to a man next to me.

“After we choose the Word of the Year?” he asked. “Pillaging. I expect downtown Portland to be wrecked.” He paused. “That’s rekt,” a shorthand spelling of the word. “R-E-K-T.”

It was a bit of linguistic humor for the start of what is perhaps the year’s most anticipated lexicological event: the annual selection of the Word of the Year (also known as WOTY) by the American Dialect Society. If wordsmiths had a Super Bowl, this would be it, a place where the nation’s most well-regarded grammarians, etymologists and language enthusiasts gather to talk shop.

Photo

Room for debate at a linguistics convention.CreditDan Cronin for The New York Times

The convention itself is about more than WOTY. Attendees have their choice of lectures on vocal fry (a creaky voice vibration common among young women), an exploration of “totally awesome,” multisyllabic rhyme in hip-hop and the Cronut, as well as more “complicated and linguisticky” topics, as one of the event’s hosts put it, like “On the nucleus-offglide trajectory of the mid-back rounded vowel in California English.”

It was also a kind of Who’s Who of the linguistic elite. Among them were Geoff Nunberg, who frequently speaks alongside Terry Gross as NPR’s linguistic contributor, and Anne Curzan, a language historian, whose TED talk on what makes a word “real” has logged more than a million views. There was the forensic linguistics pioneer Roger Shuy, who has testified in dozens of criminal court cases, as well as Michael Adams, the author of “Slayer Slang,” a 285-page investigation into the language of “Buffy the Vampire Slayer.”

But as far as WOTY went, this convention was special. It was the event’s 25th anniversary. From “Not!” — the 1992 selection, a “Wayne’s World” classic — to “chad” (the hanging bits of paper that almost swayed the 2000 presidential election), this year’s vote had drawn the largest crowd to date.

The rules for WOTY selection are simple: Anyone, including the public, can participate. Words can be nominated from the floor (perhaps the only time you’ll see a linguist shout). And the terms should be “newish,” said Ben Zimmer, the chairman of the new words committee and the event’s M.C. Though the contest is called, yes, word of the year, multiword expressions are allowed (to the chagrin of some purists).

By the time the linguists had arrived on this dreary Friday evening, a shortlist had been printed, the result of a small nominating ceremony the night before.

Among the finalists, in the “most creative” category, was “manspreading,” when a man spreads his legs on public transportation, blocking other seats (A woman quipped from the floor: “Really, men. People want to sit next to you!”), and “narcisstick,” a pejorative term for the selfie stick.

There were serious words like Ebola, as well as “platisher,” a blend of “platform” and “publisher” that Grant Barrett, the host of a linguistic radio show, deemed the “ugliest word of 2014.” “PEOPLE JUST VOMITED,” he typed onto the projection screen.

Being that this year’s event was in Portland, it was only fitting that the “lumbersexual” (a fashionably rugged man who adopts the dress and facial hair of a lumberjack) was included in the “most unnecessary” category.

“Sometimes the words are just fun,” said Tyler Schnoebelen, a San Francisco-based linguist who looked not un-lumbersexual in a chunky sweater and beard.

But, he added, “There is something beautiful about a perfectly chosen word or phrase.”

This year, the linguists decided that neither emoji nor emoticons would be considered among the entries, despite the pleas of Gretchen McCulloch, the editor of the language blog at Slate, who vowed to argue for it again next year. But the hashtag was given its own category for the first time. Among the “most notable hashtags” were #yesallwomen, spawned in the wake of the shooting near the University of California, Santa Barbara; #icantbreathe, the final words of Eric Garner; and #blacklivesmatter, which has become a rallying cry against racial injustice after the killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo.

“It’s exciting to see the hashtag be taken as a viable linguistic unit,” said Allison Shapp, a 28-year-old who is studying language on Twitter.

Yet while a contest of the most topical words may be good for press — indeed, Oxford, Merriam-Webster and Dictionary.com all have their own WOTYs now, too — it doesn’t mean the terminology will endure. Back when the American Dialect Society’s contest began in 1990, Mr. Metcalf, the society’s executive secretary, hoped it would bring the joy of wordplay to the masses. Then again, the first winner was a head-scratcher: “Bushlips,” to describe insincere political rhetoric.

As Mr. Zimmer explained, “It was a reference to George H. W. Bush’s promise of ‘Read my lips: No new taxes.’ But now it just sounds. ...”

Dirty? Unintelligible?

“It’s true that things that seem very zeitgeisty at the moment may be incomprehensible to future generations,” he said.

That’s particularly true these days, as each new word seems more memey than the last. Linguists now use Twitter to study word patterns, and many of this year’s nominations originated online, including “Columbusing,” to define acts of cultural appropriation (i.e., Columbus “discovering” America).

“The word I will always regret not voting for is nomnomnom,” Mr. Schnoebelen said, referring to the voracious onomatopoeic eating sounds of Cookie Monster (think, “om nom nom nom!”). That entry lost to “app” in 2010.

“I remember distinctly the linguist who nominated nom saying that ‘A vote for nomnomnom is a vote for joy,' ” Mr. Schnoebelen said. “I think she was right.”

Meanwhile, in the back of the room, two young women explained to an older attendee what a “bae” was (another word for a beau). Which makes “baeless” a person without a bae (i.e., single).

At the suggestion of “conscious uncoupling,” made infamous by Gwyneth Paltrow and Chris Martin, there were audible groans. But there was lively discussion of “budtender,” part of the new vernacular of legal marijuana to describe a bartender for pot. “Marijuana dispensaries are only going to increase,” a woman in the front said.

And then there was “basic,” which began in hip-hop but has come to define a certain breed of human (usually female) who likes mainstream products and is probably wearing Uggs. (“Drinking pumpkin lattes, wearing leggings,” said Jane Solomon, a lexicographer at Dictionary.com.)

“Basic! Basic! Basic!” younger linguists began to chant.

Mr. Zimmer called the crowd to order. There were only a few minutes remaining.

The final vote would prove a rare moment when a room of linguists would all agree: #blacklivesmatter should be Word of the Year.

As a political statement, it was a virtual lock. But, naturally, the debate over its linguistic validity had just begun.

“By what manner of well-meaning legerdemain,” the linguist Jonathan Lighter, a slang expert, later asked, “does a three-word Most Notable Hashtag become Word of the Year?”

Fred Shapiro, a Yale law librarian, asked, “So I guess there is no real distinction between ‘word of the year’ and ‘quotation of the year’?”

Ms. Shapp explained that one must understand “that what makes a word a word is not even a settled concept in our world.”

This, it seemed, was a very modern new word order.

​An earlier version of this article described the location of a mass shooting in 2014 incorrectly. It was near the University of California, Santa Barbara, not on the campus.

+7 (495) 969-87-46

+7 (495) 969-87-46